Integrated Music Theory 2018-19

13a Lesson - The Period

Class discussion

Further reading

From Open Music Theory

Periods

A period is one type of theme, like the sentence, common to the Classical style.

The period is generally eight measures long and contains two four-measure phrases, called antecedent and consequent.

The period is characterized by balance and symmetry. Its antecedent phrase is initiated by a basic idea that recurs at the beginning of the consequent phrase. Unlike the sentence, which exhibits a single cadence, the period contains two cadences, a weak one to end the antecedent and a strong one to end the consequent.

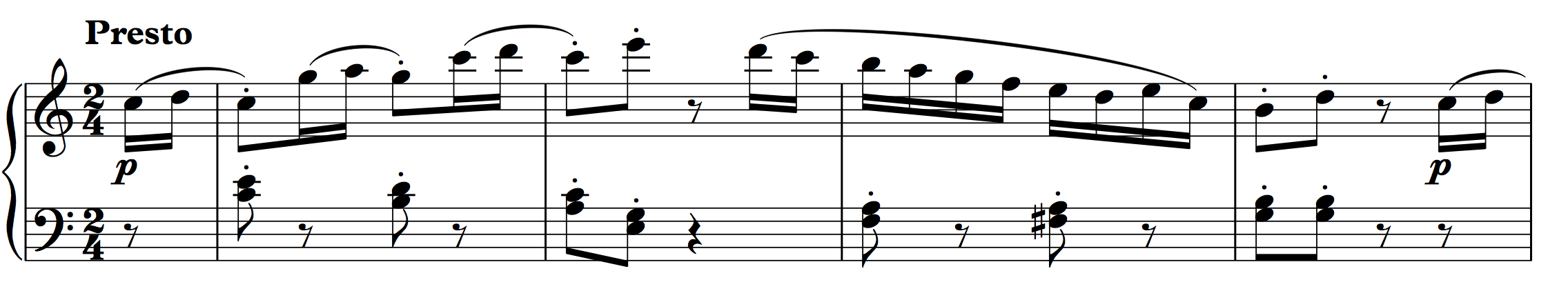

Antecedent phrase (mm. 1–4)

Unlike the sentence, which contains a basic idea followed by a repetition, the two measure basic idea that begins the a period’s antecedent is always followed by a two-measure contrasting idea (CI). That contrasting idea supports a cadential progression that ends the antecedent with a weak cadence, either a HC or an IAC.

Note the contrast created between the basic idea and contrasting idea. While the BI ascends, outlining the tonic triad with leaps to each of its members, the CI descends stepwise leading to a weak I:HC. The emphasis on tonic in the melody of the BI is accompanied by a tonic prolongation in the harmony (a variant of the Romanesca schema):

I V6 VI III

or

T(1 D7p x6 3)

Supporting the CI is an expanded cadential progression:

III IV V6/5/V V

or

T3 S(4 [+]) D5

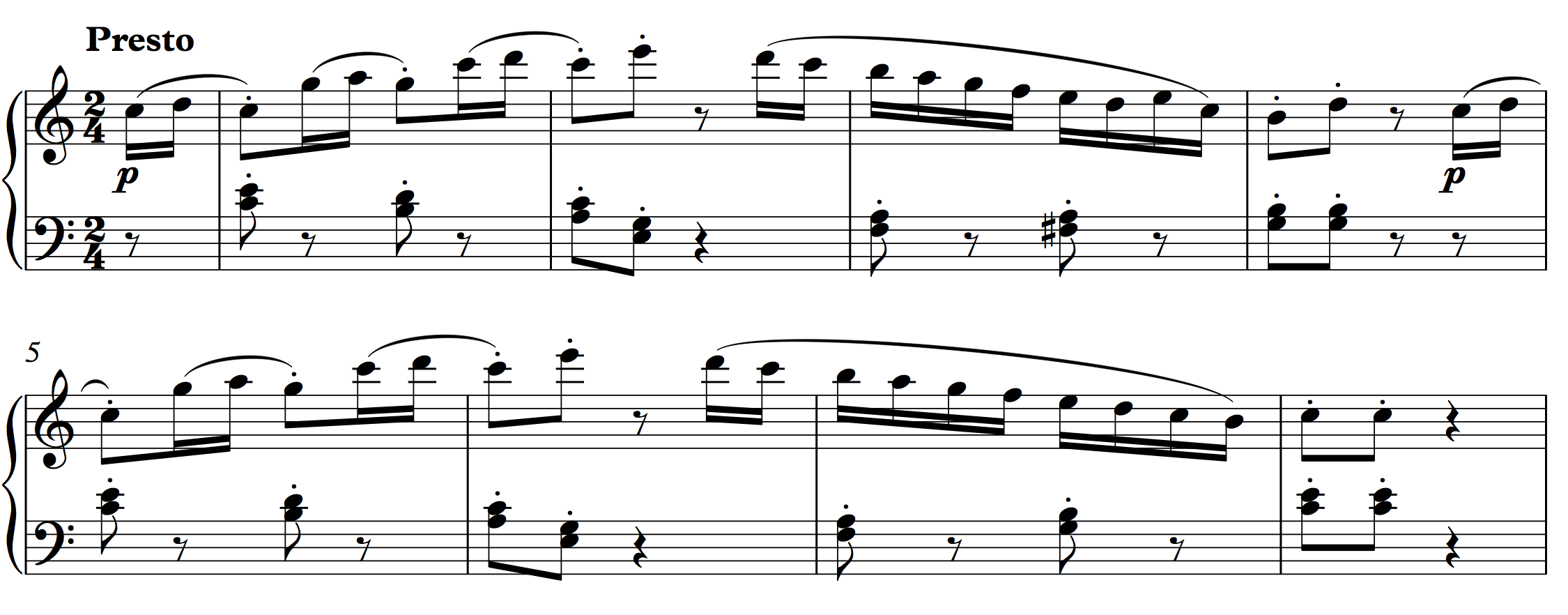

Consequent phrase (mm. 5–8)

Consequent phrases always begin with a restatement of the BI, occasionally varied, and end with a CI. A consequent phrase’s CI often resembles the antecedent’s, but slightly altered to accommodate a stronger cadence. It is also common for a consequent phrase’s CI to be entirely new. While a sentence can close with a number of cadence types, the period’s consequent phrase always ends with a PAC:

In this example, the BI is restated exactly at the beginning of the consequent. The concluding CI is a slight variation of the end of the antecedent, altered here to create a PAC.