Integrated Music Theory 2018-19

9a Lesson - Non-chord Tones

NOTE: The full descriptions below of each type of non-chord tone are from the online textbook, Open Music Theory, although each has been edited to suit this textbook’s terminology and purpose. If you have not had a chance to check out Open Music Theory in the Further Reading sections from the previous units, please take the time to do so. It is an excellent resource!

Non-chord tone recap

Understanding non-chord tones is critical in increasing the accuracy and speed of your tonal analysis. When looking at pieces of music, specifically those that have complicated textures, you will often face difficult decisions about which tones are functional to the chord and progression and which tones are embellishing those functional tones. If you know the shapes that chord tones and their embellishments form, you can separate chord tones from embellishments by simply looking for common patterns.

Labeling non-chord tones

When we study non-chord tones we label a single pitch that does not belong to the chord, however, we are actually classifying the motion between the non-chord tone and its surrounding pitches, and you can see this in how we defined the three non-chord tones (NCTs) that we studied in our counterpoint unit:

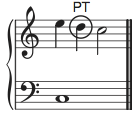

- A passing tone (PT) is a non-chord tone which is approached by step and left by step in the same direction.

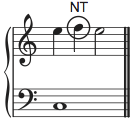

- A neighbor tone (NT) is a non-chord tone which is approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction.

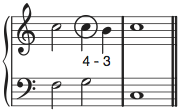

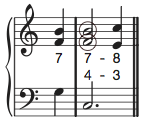

- A suspension (SUS) is a non-chord tone which is approached by static motion and resolves downward by step.

As you can see, each definition describes the motion to and from the NCT, so to facilitate discussions of NCTs, there are formal names for each pitch involved in the creating the “shape” of a non-chord tone:

- the preparation

- The pitch that directly precedes the NCT.

- Its relationship to the NCT will define the type of movement used to approach the NCT.

- the non-chord tone

- The NCT must not be a member of the chord.

- This should seem obvious given the name, but this is the most common mistake that students make when looking for NCTs.

- The NCT must not be a member of the chord.

- the resolution

- The pitch that directly follows the NCT.

- Its relationship to the NCT will define the type of movement used to leave the NCT.

Further non-chord tone terminology

This information provides a methodology and framework through which we can look at all non-chord tones, but we need further language to describe the function and characteristics of any non-chord tone.

- Accented vs unaccented

- An accented NCT occurs in a strong metric position (“on the beat”).

- An unaccented NCT occurs in a weak metric position (“off the beat”).

- On-chord vs off-chord

- An on-chord NCT coincides with a change of harmony.

- An off-chord NCT does not coincide with a change of harmony.

- Chromatic vs diatonic

- Diatonic NCTs use only the notes present in the key-signature whereas chromatic NCTs have an accidental.

- All types of NCTs can be either chromatic or diatonic, although some are extremely rare (such as a chromatic suspension).

- There are other possibilities for labeling NCTs such as ascending/descending and upper/lower. These are only applicable to certain NCTs, so it is easier to discuss these labels in those contexts.

- Passing tones can be either ascending or descending.

- Neighbor tones can be either upper or lower.

We will use the following simple progression as a template for demonstrating non-chord tones. Start by creating a Roman numeral analysis with leadsheet symbols.

Using this framework we can add some of the NCTs that we have already studied. The following exercise incorporates multiple examples of each type of NCT to create an (overly) embellished example. Identify each of the non-chord tones.

Conclusions

A passing tone is a melodic embellishment that occurs between two stable tones, creating stepwise motion. It is approached by stepwise motion and left by stepwise motion in the same direction. The typical figure is chord tone – passing tone – chord tone, filling in a third (see example), but two adjacent passing tones can also be used to fill in the space between two chord tones a fourth apart–a double passing tone. A passing tone can be either accented or unaccented as well as on-chord or off-chord.

Neighbor Tone (NT)

Like the passing tone, a neighbor tone is a melodic embellishment that occurs between two stable tones; however, a neighbor tone occurs between two instances of the same stable tone. It is approached by stepwise motion and left by stepwise motion in the opposite direction. Also like the passing tone, movement from the stable tone to the neighbor tone and back will always be by step. A neighbor tone can be either accented or unaccented, but unaccented is more common. It can also be either on-chord or off-chord.

Suspension (SUS)

A suspension is formed of three critical parts: the preparation (accented or unaccented), the suspension itself (accented), and the resolution (unaccented). The preparation is a chord tone (consonance). The suspension is the same note as the preparation and will always be on-chord. The suspension then resolves downward by step to the resolution, which occurs over the same harmony as the suspension. The suspension is in many respects the opposite of an anticipation (see below); if the anticipation is an early arrival of a tone belonging to the following chord, a suspension is a lingering of a chord tone belonging to the previous chord that forces the late arrival of the new chord’s chord tone. However, in composition and improvisation, the suspension must be treated with a great deal more care than an anticipation. The most common suspensions (and their resolutions) in upper voices form the following intervallic patterns against the bass: 9–8, 7–6, 4–3. (With the exception of 9–8, the pitch class of the resolution tone should never sound in another voice simultaneous with the suspended tone.) You should label suspensions by adding the intervallic pattern against the bass to the abbreviation “sus”; if the suspension is in the bass, please label the intervals against the most dissonant voice. (In a four-part harmony, this will almost always result in a 2-3 suspension.)

More non-chord tones

There are many other types of NCTs, and we can use our simple progression to demonstrate examples of each of them. Compare the examples below to the original progression to determine what has changed; this change is the NCT. As you do this, use the the three characteristics discussed in the overview – preparation, NCT, and resolution – to create a definition for each NCT. Once you have a working definition, see if the other other descriptors (such as upper/lower, ascending/descending, chromatic/diatonic, on-chord/off-chord or accented/non-accented) can be applied to each NCT.

Retardations (RET)

Which other NCT does a retardation resemble?

Conclusion (RET)

A retardation is essentially an upward-resolving suspension. It is almost always reserved for the final chord of a large formal division (or a movement), and it frequently appears simultaneously with a suspension (as seen in the example). Like suspensions, retardations must be accented and on-chord, yet unlike suspensions, it is not necessary to label the intervals against the bass, although you may if you wish.

Neighbor Groups (NG) - also called “double neighbor tones”

How does the neighbor group relate to a neighbor tone?

Conclusions

Like neighbor tones, a neighbor group, also known as a double neighbor figure, begins and ends on the same stable tone. Between those two instances of the stable tone are two embellishing tones — one a step above and the other a step below the stable tone being embellished. Though individually we may consider each of the two embellishing tones to be incomplete neighbor tones, working together in the double-neighbor figure, they balance each other and create a contiguous whole, with the overall stability of a complete neighbor. A double neighbor figure is typically unaccented and off-chord, although it could be either accented and on-chord.

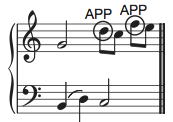

Appoggiaturas (APP)

In the same way that suspensions and retardations are often grouped together, appoggiaturas and escape tones are as well. The following two examples include NCT appoggiaturas and escape tones as well as appoggiaturas figures and escape tone figures. Use the example below to answer the following:

- What is the definition for both of these non-chord tones?

- What do they have in common and why are they grouped together?

- What major difference does the term “figure” imply when used in referencing non-chord tones? Do you think that “figure” could be applied to any of the previous NCTs that we have studied?

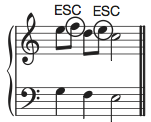

Escape tones (ET)

Conclusions

An appoggiatura is a kind of incomplete neighbor tone that is approached by leap, and followed by step in the opposite direction.

An escape tone, or echappée, is approached by stepwise motion and left by leap in the opposite direction.

The term “figure” can be used when discussing non-chord tones to imply that the melody follows the shape of a particular non-chord tone, but all pitches are actually chord tones. This is very useful in describing melodic shapes. (e.g. A melody can be described as having a passing tone figure if the melody has a stepwise movement continuously in one direction, even if every note belongs to a chord.)

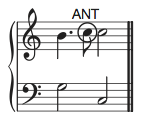

Anticipations (ANT)

Conclusions

An anticipation is essentially an otherwise stable tone that comes too early. An anticipation is a non-chord tone that will occur immediately before a change of harmony, and it will be followed on that change of harmony by the same note, now a chord tone of the new harmony. Therefore, it is approached by stepwise motion and left by static motion. The static motion between the NCT and its resolution means that you may consider this related to both suspensions and retardations, although unlike suspensions and retardations, this is an unaccented, off-chord NCT with static motion occurring after the NCT rather than before. It is typically found at the ends of phrases and larger formal units.

Some theorists classify syncopated rhythmic figures as separate from anticipations, but this is more a discussion of re-articulation. For those that classify these differently, syncopation occurs when a rhythmic pattern that typically occurs on strong beats or strong parts of the beat occurs instead on weak beats or weak parts of the beat. Like the anticipation, the syncopated note is an early arrival — it tends to belong to the chord on the following beat. Unlike the anticipation, the syncopation is tied into a note in that chord and is not rearticulated. Rather than anticipating a note in the chord that follows, a syncopation is simply an early arrival. Of course, you should consider context when making this decision as this difference is subtle, but if there is a pattern of syncopated rhythms in a passage, you could be more likely to label a syncopation.

Pedals (PED)

Pedals, often referred to as pedal points, most often occur in the bass voice but can occur in any voice. They can be difficult to spot if the texture is broken into arpeggiated chords, so it may be necessary to reduce a complicated texture down to block chords to more easily find the pedals.

Conclusions

Pedals are approached by static motion and left by static motion; essentially, this is just a pitch that refuses to leave regardless of whether it belongs to the chord. Pedals are one of the most interesting non-chord tones because they have a dual nature–they create some of the strongest dissonances in tonal harmony, but their repetitive nature provides a sort of strange stability. As a pedal continues, it will often alternate between acting as a chord tone and non-chord tone, so it can be helpful to label the chord tones as “pedal figures” to show the continuation of the pedal.

Less common non-chord tones

Incomplete Neighbor Tone (INT)

It is uncommon, but you will occasionally encounter an unaccented non-chord tone that is approached by leap and left in the same direction; resembling an appoggiatura but not resolving in the opposite direction. For this course, we will label these as incomplete neighbor tones, although some theorists use this term to refer to appoggiaturas and escape tones as well. Broadly speaking, you should not resort to an incomplete neighbor tone NCT unless you have exhausted all other options, because it is far more likely for this shape is part of a chordal skip rather than an NCT.