Integrated Music Theory 2018-19

Discussion 5c - 2:1 Counterpoint and Embellishing Shapes

Class discussion

TBD

Further reading

From Open Music Theory

Embellishing tones

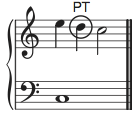

Passing Tone (PT)

A passing tone is a melodic embellishment (typically a non-chord tone) that occurs between two stable tones (typically chord tones), creating stepwise motion. The typical figure is chord tone – passing tone – chord tone, filling in a third (see example), but two adjacent passing tones can also be used to fill in the space between two chord tones a fourth apart. A passing tone can be either accented (occurring on a strong beat or strong part of the beat) or unaccented (weak beat or weak part of the beat).

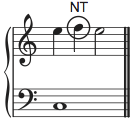

Complete Neighbor Tone (NT)

Like the passing tone, a complete neighbor tone is a melodic embellishment that occurs between two stable tones (typically chord tones); however, a complete neighbor tone will occur between two instances of the same stable tone. Also like the passing tone, movement from the stable tone to the neighbor tone and back will always be by step. A complete neighbor can be either accented or unaccented, but unaccented is more common.

Double Neighbor Figure (DN)

Like the complete neighbor figure, the double neighbor figure begins and ends on the same stable tone (typically a chord tone). Between those two instances of the stable tone are two embellishing tones — one a step above and the other a step below the stable tone being embellished. Though individually we may consider each of the two embellishing tones to be incomplete neighbors (below), working together in the double-neighbor figure they balance each other out and create a contiguous whole, with the overall stability of a complete neighbor. A double neighbor figure is typically unaccented.

Incomplete Neighbor Tone (INT)

The incomplete neighbor tone is an unaccented embellishing tone that is approached by leap and proceeds by step to an accented stable tone (typically a chord tone). Broadly speaking an incomplete neighbor tone is any embellishing tone a step away from a stable tone that proceeds or follows it (and is connected on the other side by leap), but other kinds of incomplete neighbor tones have special names and roles that follow below.

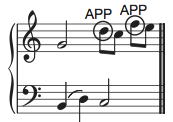

Appoggiatura (APP)

An appoggiatura is a kind of incomplete neighbor tone that is accented, approached by leap (usually up), and followed by step (usually down, but always in the opposite direction of the preceding leap) to a more stable tone (typically a chord tone).

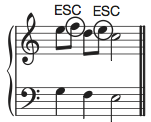

Escape Tone (ESC)

An escape tone, or echappée, is a kind of incomplete neighbor tone that is unaccented, preceded by step (usually up) from a chord tone, and followed by leap (usually down, but always in the opposite direction of the preceding step).

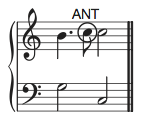

Anticipation (ANT)

An anticipation is essentially an otherwise stable tone that comes too early. An anticipation is typically a non-chord tone that will occur immediately before a change of harmony, and it will be followed on that change of harmony by the same note, now a chord tone of the new harmony. It is typically found at the ends of phrases and larger formal units.

Syncopation (SYN)

Syncopation occurs when a rhythmic pattern that typically occurs on strong beats or strong parts of the beat occurs instead on weak beats or weak parts of the beat. Like the anticipation, the syncopated note is an early arrival — it tends to belong to the chord on the following beat. Unlike the anticipation, the syncopation is tied into a note in that chord; it is not rearticulated. Rather than anticipating a note in the chord that follows, a syncopation is simply an early arrival.

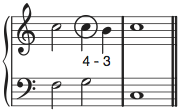

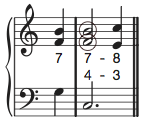

Suspension (SUS)

A suspension is formed of three critical parts: the preparation (accented or unaccented), the suspension itself (accented), and the resolution (unaccented). The preparation is a chord tone (consonance). The suspension is the same note as the preparation and occurs simultaneous with a change of harmony. The suspension then proceeds down by step to the resolution, which occurs over the same harmony as the suspension. The suspension is in many respects the opposite of the syncopation: if the anticipation is an early arrival of a tone belonging to the following chord, a suspension is a lingering of a chord tone belonging to the previous chord that forces the late arrival of the new chord’s chord tone. However, in composition and improvisation, the suspension must be treated with a great deal more care than the syncopation. The most common suspensions (and their resolutions) in upper voices form the following intervallic patterns against the bass: 9–8, 7–6, 4–3. (With the exception of 9–8, the pitch class of the resolution tone should never sound in another voice simultaneous with the suspended tone.) Instead of SUS, it is more typical to notate the intervallic pattern in the thoroughbass figures.

Retardation (RET)

A retardation is essentially an upward-resolving suspension. It is almost always reserved for the final chord of a large formal division (or a movement), and it frequently appears simultaneously with a suspension (as seen in the example). Instead of RET, it is preferable to notate the intervallic pattern in the thoroughbass figures.

Second species counterpoint

The counterpoint line

As in first species, the counterpoint line should be singable, have a good shape, with a single climax and primarily stepwise motion (with some small leaps and an occasional large leap for variety). However, because a first-species counterpoint had so few notes, in order to maintain smoothness in other aspects of the exercise, the melody frequently employed small leaps. In second species, the increase in notes and the added freedom involving the use of dissonance makes it easier to move by step without causing other musical problems. Thus, a second-species counterpoint is even more dominated by stepwise motion than in first species.

If the counterpoint must leap, take advantage of the metrical arrangement to diminish the attention drawn to the leap: leap from strong beat to weak beat (within the bar) rather than from weak beat to strong beat (across the barline) when possible.

Also, because there are more notes in a second species line, there should usually be one or two secondary climaxes—notes lower than the overall climax that serve as “local” climaxes for portions of the line. This will help the integrity of the line, by ensuring it has a coherent shape and does not simply wander around.

Beginning a second-species counterpoint

As in first species, begin a second-species counterpoint above the cantus firmus with do or sol. Begin a second-species counterpoint below the cantus firmus with do. Unisons are permitted for the first and last dyads of the exercise.

A second-species line can begin with two half notes in the first bar, or a half rest followed by a half note. Beginning with a half rest establishes the rhythmic profile more readily, making it easier for the listener to parse, so it is often preferable. It is also easier to compose. Regardless of rhythm, the first pitch in the counterpoint should follow the intervallic rules above.

Ending a second-species counterpoint

The final pitch of the counterpoint should be do, as in first species.

The penultimate note of the counterpoint should be ti if the cantus is re, and re if the cantus is ti, as in first species.

The penultimate bar of the counterpoint can either be a whole note (making the last two bars identical to first species), or two half notes. Which option you use will depend on how you are approaching the final bar. (This is simply a historical convention, not a musical necessity. But the added degree of freedom makes it easier to move into the final arrival smoothly without adding too many complicating factors.)

Strong beats

Because the inclusion of dissonance in a musical texture creates new musical problems that need to be addressed, second species introduces dissonance in a very limited way. This is not a musical necessity, and it’s not the only way to address dissonance, but it helps by introducing a small number of new musical difficulties in each species.

Strong beats (downbeats) in second species are always consonant. As in first species, prefer imperfect consonances (thirds and sixths) to perfect consonances (fifths and octaves), and avoid unisons.

Because motion across bar lines (from weak beat to strong beat) involves the same kind of voice motion as first species (two voices moving simultaneously), follow the same principles as first species counterpoint. For instance, if a weak beat is a perfect fifth, the following downbeat must not also be a perfect fifth.

Likewise progressions from downbeat to downbeat must follow principles of first-species counterpoint. The following are some examples, but not an exhaustive list:

- Do not begin two consecutive bars with the same perfect interval.

- Do not outline a dissonant melodic interval between consecutive downbeats. (Exception: if the counterpoint leaps an octave from the strong beat to the weak beat, the leap should be followed by step in the opposite direction making a seventh with the preceding downbeat. This is okay, since it is the result of smooth voice motion.)

- Do not begin more than three bars in a row with the same imperfect consonance.

Hidden or direct fifths/octaves between successive downbeats are fine, as the effect is weak, and the intervening note in the counterpoint diminishes that effect.

Weak beats

Since harmonic dissonances can appear on weak beats, a mixture of consonant and dissonant intervals on weak beats is the best way to promote variety.

Unisons were problematic in first species because they diminished the independence of the lines. However, when they occur on the weak beats of second species and are the result of otherwise smooth voice-leading, the rhythmic difference in line is sufficient to maintain that independence. Thus, unisons are permitted on weak beats when necessary to make good counterpoint between the lines.

Any weak-beat dissonance must follow the pattern of the dissonant passing tone, explained below. Also explained below are a number of standard patterns for consonant weak beats. Chances are high that if your weak beats do not fit into one of the following patterns, there is a problem with the counterpoint, so use them as a guide both for composing the counterpoint, and for evaluating it.

Weak beat patterns

The following patterns (whose terms are either standard or taken from Salzer & Schachter’s Counterpoint in Composition) should guide your use of weak-beat notes in a second-species counterpoint line. A good general practice is to start with a downbeat note, then choose the following downbeat note, and finally choose a pattern below that will allow you to fill in the space between downbeats well.

Most of these are used as examples in the demonstration video at the bottom of the page.

Dissonant weak beats

All dissonant weak beats in second species are dissonant passing tones, so called because the counterpoint line passes from one consonant downbeat to another consonant downbeat by stepwise motion. The melodic interval from downbeat to downbeat in the counterpoint will always be a third, and the passing tone will come in the middle in order to fill that third with passing motion.

Since all dissonances in second species are passing tones, you will never leap into or out of a dissonant tone, nor will you change directions on a dissonant tone, nor will any dissonances occur on a downbeat.

Consonant weak beats

A consonant passing tone outlines a third from downbeat to downbeat, and has the same pattern as the dissonant passing tone, except that all three tones (downbeat, passing tone, downbeat) are consonant with the cantus. A consonant passing tone will always be a sixth or perfect fifth above/below the cantus.

A substitution also outlines a third from downbeat to downbeat. However, instead of filling it in with stepwise motion, the counterpoint leaps a fourth and then steps in the opposite direction. It is called a substitution because it can substitute for a passing tone in a line that needs an extra leap or change of direction to provide variety. Like the consonant passing tone, all three notes in the counterpoint must be consonant with the cantus.

A skipped passing tone outlines a fourth from downbeat to downbeat. The weak-beat note divides that fourth into a third and a step. Again, all three intervals (downbeat, skipped passing tone, downbeat) are consonant with the cantus.

An interval subdivision outlines a fifth or sixth between successive downbeats. The large, consonant melodic interval between downbeats is divided into two smaller consonant leaps. A melodic fifth between downbeats would be divided into two thirds. A melodic sixth between downbeats would be divided into a third and a fourth, or a fourth and a third. Not only must all three melodic intervals be consonant (both note-to-note intervals and the downbeat-to-downbeat interval), but each note in the counterpoint must be consonant with the cantus.

A change of register occurs when a large, consonant leap (P5, sixth, or octave) from strong beat to weak beat is followed by a step in the opposite direction. It is used to achieve melodic variety after a long stretch of stepwise motion, to avoid parallels or other problems, or to get out of the way of the cantus to maintain independence. It should be used infrequently. And as always, each note must be consonant with the cantus.

A delay of melodic progression outlines a step from downbeat to downbeat. It involves a leap of a third from strong beat to weak beat, followed by a step in the opposite direction into the following downbeat. It is called a “delay” because it is used to embellish what otherwise is a slower first-species progression (motion by step from downbeat to downbeat).

A consonant neighbor tone occurs when the counterpoint moves by step from downbeat to weak beat, and then returns to the original pitch on the following downbeat. If the first downbeat makes a fifth with the cantus, the consonant neighbor will make a sixth, and vice versa.

Demonstration

In the following video, I illustrate the process of composing a second-species counterpoint. This video provides new information about the compositional process, as well as concrete examples of the above rules and principles.