Integrated Music Theory 2023-24

Class reading - An introduction to basso continuo keyboard-style voice-leading

Class reading

From Open Music Theory

Modified for this website by Sean Butterfield

Basso continuo emerged in the seventeenth century as a shorthand notation for keyboardists (typically church organists) who were accompanying a soloist or small ensemble performing a work originally composed for a larger group. For example, if two or three singers were tasked with performing an eight-voice choral work, they could select the most prominent parts to sing, while an organist could cover the rest. Performing five or six lines of contrapuntal choral music could be a significant challenge, so organists needed a way to condense the texture while still preserving the core musical structure to support the vocalists.

The thorough bass emerged as that shortcut. The “thorough” or “continuous” bass is a musical line that includes the lowest note at any given time. Usually, works would not include a single part that could function as this line, so the organist would alternate between voices, as they exchanged registers or took rests. The resulting line, unlike the regular “bass” part, was “continuous” (or “thorough”)—hence the name thoroughbass or basso continuo.

A good musician could perform this bass line, and with an eye (or ear) on the vocal parts and with knowledge of how to improvise good voice-leading, that musician could accompany the thoroughbass line with chords that made musical sense. (This is the original meaning of the term accompany—to accompany a bass line with chords. The fact that keyboardists did this in the context of supporting a soloist or small ensemble led to that term later being applied to any situation where a keyboardist accompanied spotlight performers.)

As this technique grew, publishers began publishing thoroughbass reductions of large-ensemble pieces to support smaller groups of musicians. In these publications, figures (numbers above or below the bass line) were included—sometimes only for difficult or non-standard chords, and eventually for most chords, enabling more amateur musicians, as well as students, to make use of the technique. These bass lines with figures became known as “figured bass” lines.

J.S. Bach, Flute Sonata in C Major, ii., BWV 1033. The upper part is played by the flute, the lower part is the basso continuo line, played by a keyboardist who uses the numbers below the staff (figures) to guide the chords played above this bass line.

To this day, harpsichordists performing in Baroque ensembles will often put their left hand to the same “bass” line that the cellos play, and will improvise right-hand chords (with contrapuntally sound embellishment) according to the figures provided with the bass line.

Though most music students are not Baroque keyboard specialists in training, thoroughbass, or basso continuo, can be a valuable tool in the study of harmony and voice-leading. In the study of harmony, a thoroughbass line can play a valuable role as a harmonic reduction of a complex texture, in order to example and understand better the harmonic skeleton underlying a passage. In aural dictation, transcription, and analysis, the bass line and the melody are often the most prominent (and most important) lines in a passage, and knowing how the inner voices tend to relate to the bass line and melody can aid in a number of listening and aural-analysis tasks. In voice-leading, the basso continuo texture affords a straightforward environment in which to make a gradual, staged progression through the intricacies of writing musical lines in a harmonic texture—and to do so without paying significant attention to harmony.

Basso continuo (It. for “continuous bass” or “thoroughbass”) is essentially a chordal version of first-species counterpoint. However, instead of composing a single line above a cantus firmus, one composes a succession of chords (performed in the right hand) above a bass line (performed in the left hand). Basso continuo writing, also referred to as realizing a figured bass, gives no consideration to melody, only to the use of proper chords and the smoothest voice-leading possible. Thus, basso continuo style is a simple place to begin engaging the “fundamental musical problems” that arise when more than two lines are combined.

The historical origin of the thoroughbass part was in church settings where a piece for 6–8 singers was to be performed by one or two voices with a keyboard instrument. The keyboardist, rather than play the 4–7 remaining parts, would transcribe the lowest note and shorthand figures to indicate the (simple) intervals present above that lowest voice. This would allow the keyboardist to play one or two of the more important lines, and fill the rest of the texture with blocked or arpeggiated chords. (Think seventeenth-century lead sheet.) A good keyboardist, who knew their harmony and voice-leading, could simply follow the bass line without figures (an unfigured bass) and listen to the melody, improvising the rest. Less experienced keyboardists, however, could manage otherwise complicated pieces by reading a bass line and memorizing a small number of figures and basic voice-leading rules.

Coming after species counterpoint in our studies, basso continuo exercises provide a new, more complicated environment in which to practice mediating the demands of smoothness, independence of lines, tonal fusion (now considering triads and seventh chords), variety, and motion. New considerations of performability are introduced, and the presence of dissonances within the core harmonies themselves will call for new approaches to harmonic dissonance in this style.

We will use thoroughbass lines for a number of purposes in this book:

- harmonic “reductions” of pieces and passages with dense textures or complicated voice-leading

- shorthand representations of stock harmonic patterns

- the harmonic basis for model composition exercises (akin to the cantus firmus of species counterpoint)

Thoroughbass is a simple, and foundational, concept. Master it early, and subsequent activities will be much easier.

Note on figure placement: Thoroughbass figures can appear above or below the bass line. Both are common, but in this book, we generally place them above the bass line. This connects them to our habits of interval analysis during species counterpoint, keeps figures separate from other harmonic symbols we will place below the bass line, and make typesetting in notation software easier when both figures and other symbols are in play simultaneously.

Figures

In general, a thoroughbass figure indicates the simple intervals above the bass for all pitch classes present in the chord.

The largest number typically found in thoroughbass figures is 7. In general, compound intervals (an octave or larger) are reduced to their simple interval equivalent. A tenth becomes a third, a thirteenth becomes a sixth, etc.

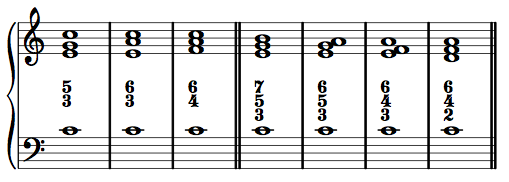

The most common chords in tonal music are triads and seventh chords. The following figures apply to these chords:

- 5/3: use a fifth and a third above the bass (one note of the chord will be doubled)

- 6/3: use a sixth and a third above the bass (one note of the chord will be doubled)

- 6/4: use a sixth and a fourth above the bass (one note of the chord will be doubled)

- 7/5/3: use a seventh, a fifth, and a third above the bass

- 6/5/3: use a sixth, a fifth, and a third above the bass

- 6/4/3: use a sixth, a fourth, and a third above the bass

- 6/4/2: a use a sixth, a fourth, and a second above the bass

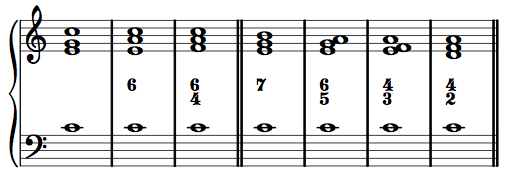

These figures are so common, that most of them have shortcuts:

- no figure = 5/3

- 6 = 6/3

- 6/4 is never abbreviated

- 7 = 7/5/3

- 6/5 = 6/5/3

- 4/3 = 6/4/3

- 4/2 (or just 2) = 6/4/2

Other shortcuts for figured bass realization generally follow two simple rules:

- Assume a fifth is present above the bass unless there is a “6” in the figure.

- Assume a third is present above the bass unless there is a “4” or a “2” in the figure.

Unfamiliar figures and chords

Only seven figures are given above. If you see a figure you do not recognize, simply follow the intervals (using the two shortcut rules). Likewise, if analyzing a chord that is not a triad or seventh chord, simply label the simple intervals you see/hear above the bass, from top to bottom in descending order: 7/6/3 or 5/4, for example. In time, you will become familiar with a number of other harmonic possibilities, and their corresponding figures.

Chords of the fifth and chords of the sixth

All chords can be categorized as either a chord of the fifth or a chord of the sixth. This distinction will be important for our study of voice-leading.

A chord of the fifth contains a fifth above the bass, but no sixth above the bass.

A chord of the sixth contains a sixth above the bass.

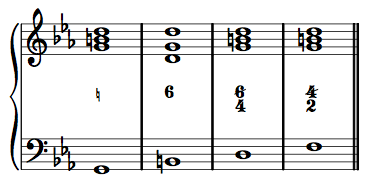

Chromatic alteration

If a note is chromatically altered (different than the key signature), the figure must be altered as well. Since bass notes are already present in the bass, a chromatic alteration in the bass will not make it into the figure. However, any other alteration in the upper voices (such as a raised leading tone in minor) must be reflected in the figure. To do so, simply put a sharp, flat, or natural to the left of the appropriate number.

Of course, there are some shortcuts. For example, draw a line (a “slash”) through a number to denote that it is raised by half-step (can substitute both for sharp or for natural). Also, when altering the third above the bass, simply use the sharp, flat, or natural and leave out the “3.”

In general, if there is a shortcut available, use it. The shortcuts are more standard than the corresponding full notation.

Keep in mind that some chords have abbreviated figures. For example, it is common for the leading tone to be the third above the bass in a 5/3 chord. In such a situation, a bass note that otherwise would have no figure needs a sharp or a natural for its thoroughbass figure.