Integrated Music Theory 2023-24

Discussion 6b - Establishing Diatonic Function through Voice Leading

Function Fun

“Why can chords have a certain pull?”

- Chords can feel like they pull when they contain contrasting notes to the established tonal center. Dissonance wants to resolve to consonance. For example, a V7 chord has a strong pull to I because it contains notes which are a half-step away from the root and third, which are essential chord tones.

- Another reason we can feel a pull is when our brains have been conditioned to hear one specific kind of resolution.

“What is a ‘circle of fifths progression’?”

- This is what we call it when the roots of the chords in a progression move in descending fifths. In Western music, this occurs extremely often. Since our brains are used to hearing this, we find it very comfortable and satisfying.

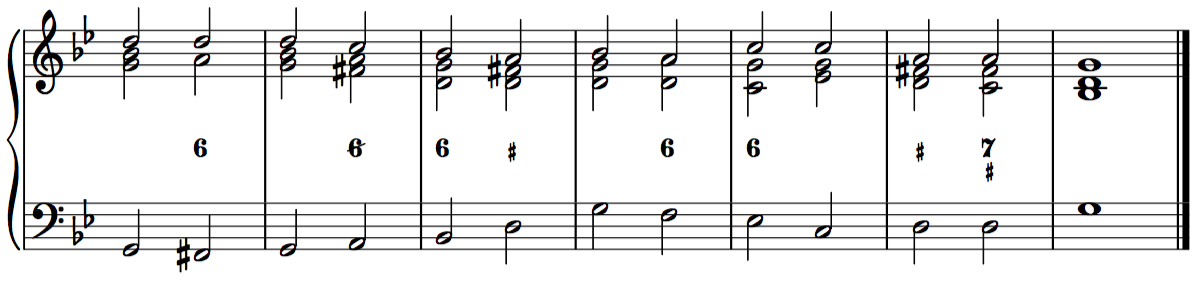

Implied Harmony in Two Parts

- You hear a V7 chord but only have the root. Why?

- We are conditioned to hear that V chord (and you just listened to a ton of them before this).

- Why is the first measure “stronger” than the second?

- The two do’s in bass and soprano voices.

- Factors that affect how “strong” something is

- People are generally better at hearing higher voices

- Inverted chords

- Intervals between voices

Harmonic functions in diatonic music

- The vi chord can be considered tonic because of shared tones with the I chord, but it has to be set up with that intention. In this class, it will not function in that way.

“How can we understand what a cadence is?”

- A cadence is like the end of a sentence. In more musical terms, we can say that cadences occur at the ends of phrases, which are implied through melody, harmony, and rhythm.

Further reading

From Open Music Theory

Chord voicing

In strict keyboard-style writing, there are four voices: the bass line (which is usually a given in basso continuo style), and three upper voices: the melody or soprano, the alto, and the tenor (from highest to lowest). Since all three upper voices must be played by a single hand, they should never span more than an octave.

The melody always has an upward-pointing stem. Alto and tenor share a downward-pointing stem. If the alto and tenor share a note, that note receives a single downward-pointing stem. (See m. 1 of the example below.) If melody and alto share a note, that notehead is double-stemmed. (See m. 4 of the example below.)

When choosing the notes to place in the upper voices above a figured bass, use the bass and figures to determine the pitch classes present in the chord. (When realizing an unfigured bass, you must determine appropriate figures before realizing.) If the chord is a four-note chord, use each chord member once, including the bass (exceptions will be noted later). If a chord has three pitch-classes (a triad, for instance), use each pitch-class once, and “double” one of them according to the following principles:

- If the figure is 6/4, 5/3, or other chord of the fifth, double the bass pitch class.

- If the figure is 6/3 and the bass is a fixed scale degree (do, re, fa, or sol), double the bass pitch class.

- If the figure is 6/3 and the bass is a variable scale degree (mi/me, la/le, or ti/te) or a chromatically altered pitch, double one of the upper voices at the octave or unison.

- Generally, do not double a variable scale degree or a chromatically altered pitch.

Tendency tones

A tendency tone is a pitch (class)—usually represented as a scale degree—that tends to progress to some pitch classes more than others. Sometimes this tendency is absolute within a style, but more often it is context-dependent.

The most prominent tendency tones in Western tonal styles are ti (not te) and le (not la).

Generally speaking, when ti appears it tends to be followed by do in the same voice. In a harmonic context, this tendency is strongest when ti occurs in a dominant-functioning chord, and the “resolution” of that tendency comes upon change of function (to tonic or predominant).

Likewise, when le appears, it tends to be followed by sol in the same voice. This tendency is less dependent on function.

Exceptions to these tendencies include:

- When ti is in the middle of a stepwise descent (re–do–ti–la–sol, for example), it can progress down by step. (Note that step inertia here diminishes the effect of an “unresolved” tendency tone. Because there are two conflicting tendencies in play, in this case, either can be “resolved” unproblematically.)

- When ti is in an inner voice, it can progress down to sol if necessary to accomplish good voice-leading in the other voices and ensure complete chords. This is called a frustrated leading-tone.

- When ti is a functional dissonance of a tonic-functioning chord (see below) it should progress down by step.

Functional dissonances

Some tendencies, such as the tendency for le to progress down, are relatively context-independent. Others are heavily contextualized. The primary contextual tendency for how melodic notes progress is the concept of functional dissonance.

Keep in mind from the Harmonic functions resource that chords tend to cluster in one of three functional groups (T, P, or D) When pitches fuse into a chord expressing one of these three functions, the pitches that comprise that have certain tendencies of progression that they may or may not have in other contexts.

Following are the scale degrees which act as dissonances for their respective functions:

| function | dissonances |

|---|---|

| T or Tx | 7, 5 when 6 is also present |

| P | 3, 1 when 2 is also present |

| D | 4, 6 |

In purely diatonic music (triads and seventh chords, no chromatics), these will include the seventh of every seventh chord, the fifth of viiº or VII (fa), and the fifth of III or iii (ti/te).

Keep in mind that only sometimes do these functional dissonances express themselves in chords or intervals that are acoustically dissonant. However, they do introduce a degree of tension that, like an acoustically dissonant interval in species counterpoint, requires a smooth introduction and a specific resolution.

When one of these scale degrees is present in a chord with the corresponding function, the dissonant scale degree has a strong tendency to resolve down by step over the next change in function. In strict composition, we will always follow these tendencies.

In strict keyboard style, these functional dissonances should be “prepared” (approached) by common tone or by step. Thus, though they are proper members of the chord, melodically they will look like one of the three dissonance types of species counterpoint: a passing tone or neighbor tone dissonance that is approached by step, or a suspension dissonance that is approached by a common tone. The suspension type is preferred.

Once a functional dissonance is introduced, it must be resolved down by step in the same voice when the function changes. The dissonance can also be transferred to another voice before resolution—for instance, if there are multiple chords in a row exhibiting the same function, a dissonance that appears in the alto can be transferred to the tenor in the following chord, and then resolve in the tenor when the function changes. (It is more typical, and smoother sounding, to transfer dissonances between inner voices or from an inner voice to an outer voice than from an outer voice to an inner voice. Once a dissonance appears in the melody or bass, where it is more noticeable, it tends to resolve in that voice.)

Functional dissonance resolutions often cause conflicts with other principles of voice leading. Except in special cases such as schemata (standard patterns that are common enough to sound appropriate, even if they follow different rules), the functional dissonance resolution takes precedence over other principles such as the law of the shortest way, contrary motion with the bass, and preferring common tones and steps to melodic leaps. A dissonance resolution is never an excuse for illegal parallels, and only rarely will lead to non-standard doublings.