Integrated Music Theory 2023-24

Discussion 2a - Diatonic Scales

Scalar Scoop

Definition of a Scale

- A pitch collection is any group of notes in any order.

- A scale is a group of notes arranged in an ascending or descending order.

- A scale must contain each of the seven note name (A,B,C,D,E,F,G).

- Scale degrees are written as numbers with a caret symbol (^) above them.

Additional pedagogical way to label a major scale:

- Tonic, Super Tonic, Mediant, Sub Dominant, Dominant, Sub Mediant, Leading Tone

“What is the difference between parallel and relative minor?”

- Parallel scales have the same tonic, relative scales share the same collection of pitches.

- Only the natural minor scale has a true relative major scale.

“Where does harmonic minor get its name?”

- Because the dominant-tonic relationship used in standard harmonic progression requires a major five chord, which needs the leading tone.

“Why do we use melodic minor?”

- It allows for tension and release in both directions. When a melody is ascending, La and Ti draw the ear up to Do. While a melody is descending, Te and Le draw the ear down to So.

“Why does melodic minor sound more correct than harmonic minor?”

- Because La and Ti want to resolve up to the tonic. When Ti is followed by Le, like in the harmonic minor version of Happy Birthday, there is an augmented second in the melody.

Interval Interlude

“How would you teach a beginner music student what an interval is?”

- It is easiest to teach a student what a scale sounds like first, then base intervals off of that.

“How can we define whole steps and half steps without scales?”

- Looking at the keyboard, a half step is the closest possible next key. A whole step is two keys away.

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

A scale is a succession of pitches ascending or descending in steps. There are two types of steps: half steps and whole steps. A half step (H) consists of two adjacent pitches on the keyboard. A whole step (W) consists of two half steps. Usually, the pitches in a scale are each notated with different letter names, though this isn’t always possible or desirable.

The major scale

A major scale, a sound with which you are undoubtedly familiar, consists of seven whole (W) and half (H) steps in the following succession: W-W-H-W-W-W-H. The first pitch of the scale, called the tonic, is the pitch upon which the rest of the scale is based. When the scale ascends, the tonic is repeated at the end an octave higher.

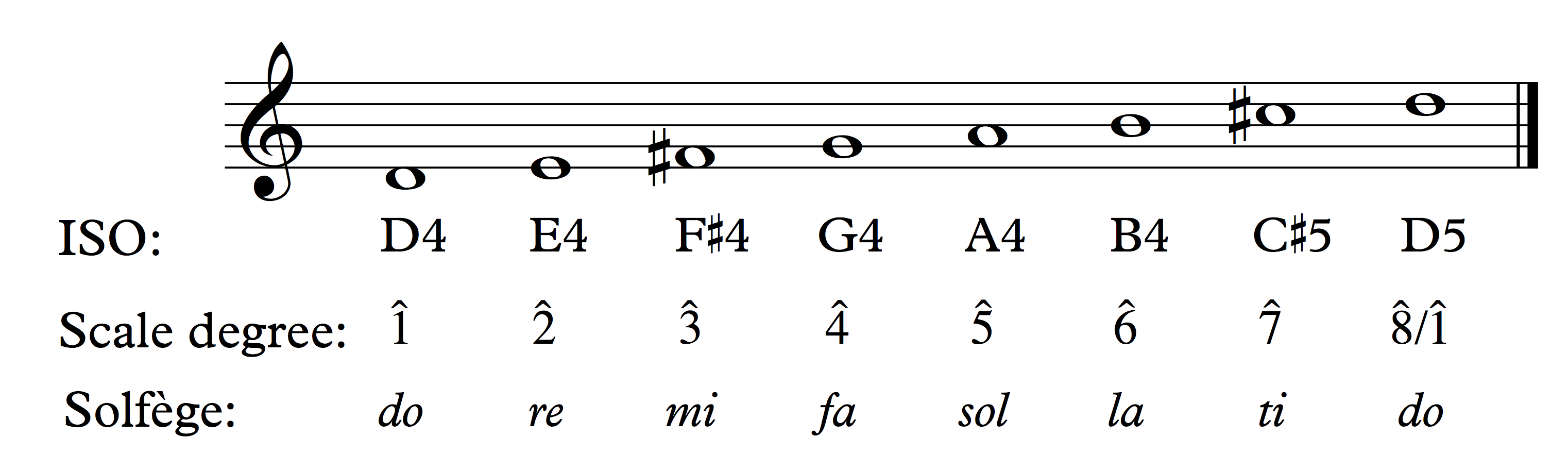

Here is the D major scale. It is called the “D major scale” because the pitch D is the tonic and is heard at both ends of the scale.

Scale degrees and solfège

While ISO notation allows us to label a pitch in its specific register, it is often useful to know where that pitch fits within a given scale. For example, the pitch class D is the first (and last) note of the D-major scale. The pitch class A is the fifth note of the D-major scale. When described in this way, we call the notes scale degrees, because they’re placed in context of a specific scale. Solfège syllables, a centuries-old method of teaching pitch and sight singing, can also be used to represent scale degrees (when used in this way, this system is specifically called movable-do solfège).

Scale degrees are labeled with Arabic numerals and carets (^). The illustration below shows a D-major scale and corresponding ISO notation, scale degrees, and solfège syllables.

The minor scale

Another scale with which you are likely very familiar is the minor scale. There are several scales that one might describe as minor, all of which have a characteristic third scale degree that is lower than the one found in the major scale. The minor scale most frequently used in tonal music from the Common Practice period is based on the aeolian mode (you’ll read more about modes later), which is sometimes referred to as the natural minor scale.

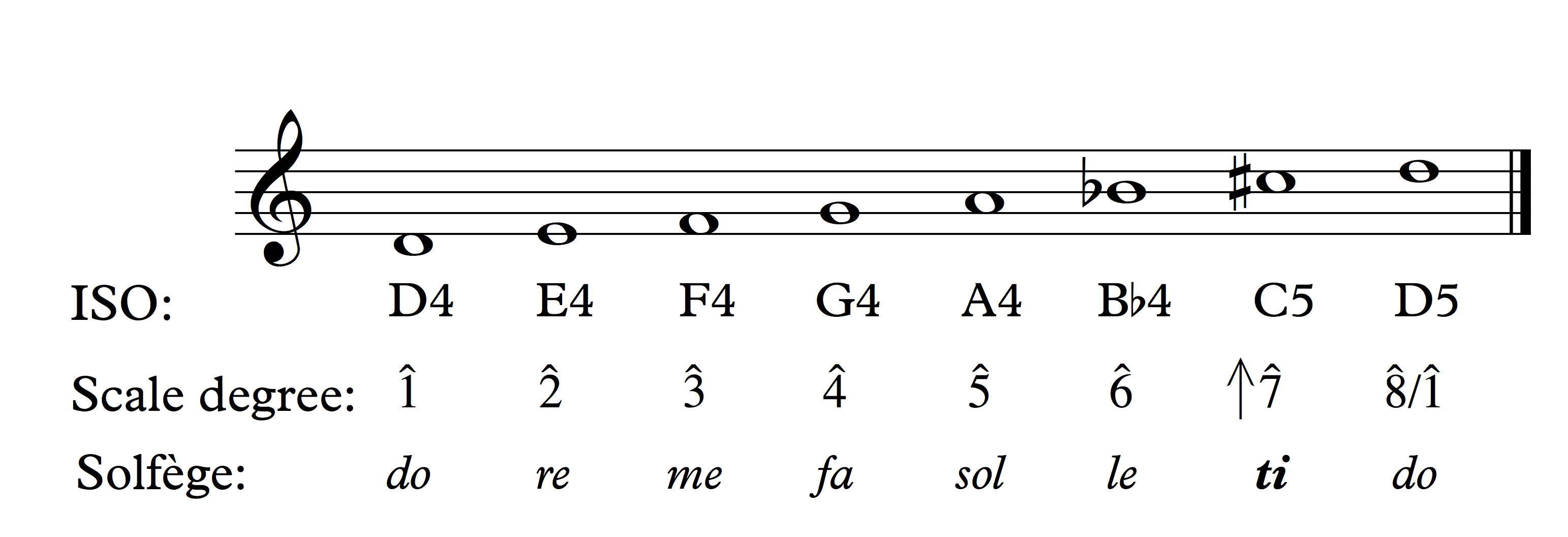

The natural minor scale consists of seven whole (W) and half (H) steps in the following succession: W-H-W-W-H-W-W. Note the changes in solfège syllables.

If you sing through the above example, you’ll notice that the ending lacks the same sense of closure you heard in the major scale. This closure is created in the major scale, in part, by the ascending semitone between ti and do. Composers often want to have this sense of closure when using the minor mode, too. They’re able to achieve this by applying an accidental to the seventh scale degree, raising it by a semitone. If you do this within the context of the natural minor scale, you get something called the harmonic minor scale.

Now the last two notes of the scale sound much more conclusive, but you might have found it difficult to sing le to ti. When writing melodies in a minor key, composers often “corrected” this by raising le by a semitone to become la when approaching the note ti. When the melody descended from do, the closure from ti to do isn’t needed; likewise, it is no longer necessary to “correct” le, so the natural form of the minor scale is used again. Together, these different ascending and descending versions are called the melodic minor scale.

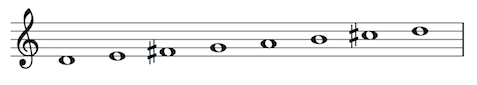

When ascending, the melodic minor scale uses la and ti.

When descending, the melodic minor scale uses the “natural” te and le.

Truth be told, most composers don’t really think about three different “forms” of the minor scale. The harmonic minor scale simply represents composers’ tendency to use ti when building harmonies that include the seventh scale degree in the minor mode. Likewise, the melodic minor scale is derived from composers’ desire to avoid the melodic augmented second interval (more on this in the intervals section) between le and ti (and some chose not to avoid this!). In reality, there is only one “version” of the minor scale. Context determines when a composer might use la and ti when writing music in a minor key.