Integrated Music Theory 2021-22

9a Lesson - Non-chord Tones, Part 1

NOTE: The full descriptions below of each type of non-chord tone are from the online textbook, Open Music Theory, although each has been edited to suit this textbook’s terminology and purpose. If you have not had a chance to check out Open Music Theory in the Further Reading sections from the previous units, please take the time to do so. It is an excellent resource!

Chord tones versus non-chord tones (NCTs)

To this point in our harmonic analyses, we have looked at mostly simple textures that utilized steady, blocked chords. To make music varied and interesting, however, we need to be able to create a variety of melodic shapes and motives, and this requires using a mixture of pitches that are functional–meaning that they are part of the harmony–and non-functional embellishments. We call these embellishing pitches non-chord tones (NCT), and understanding which pitches are functional is often the most difficult hurdle in harmonic analysis.

Much like determining the harmonic rhythm, finding NCTs can be difficult because it requires you to work through all possible combinations of the pitches within a given harmony and then choose the most likely combination. Even if you know that the harmony spans only two beats, it can be difficult to sort through all the possible combinations if the texture is complicated. Fortunately, the same strategies that work for determining the harmonic rhythm provide a foundation for determining NCTs. You can begin by looking at melodic patterns and bass-lines, and it is helpful to consider whether a note occurs in a strong or weak metric position. It is unusual for the functional tones to occur only on offbeats, as the ear is drawn to pitches when they occur on the beat.

Even for one experienced in finding patterns within the music, this still sometimes requires trial-and-error. When first learning how to identify non-chord tones, you may want to copy and rearrange the pitches on another staff (or lightly next to the chord if there is room,) to see what triads and seventh chords are even possible given the present notes. Usually this is enough to limit the possibilities to one or two chords. When it is not, you will then need to refer to your harmonic flowchart to see if there is some context that could provide a probable chord.

Discussing and labeling non-chord tones

When developing a harmonic analysis, you should place parentheses around the note head of each non-chord tone and then label the NCT with its abbreviation. Each of the non-chord tones below will have a standard abbreviation written next to the definition. (For example, passing tones will be labeled using a “pt”.)

Although before we can find non-chord tones in music, we need a shared terminology that describes how they are constructed. There are a great variety of NCTs, but every type shares a basic framework that we classify by motion between the notes on either side of it.

- the preparation

- The chord tone that directly precedes the NCT.

- Its relationship to the NCT will define the type of movement used to approach the NCT.

- the non-chord tone

- The NCT must not belong to the chord. This should be obvious given the name, but this is the most common mistake that students make when labeling NCTs.

- the resolution

- The chord tone that immediately follows the NCT.

- Its relationship to the NCT will define the type of movement used to leave the NCT.

And while these three terms provide a framework through which we can classify the movement of all non-chord tones, there are other aspects of their function and characteristics that we may need to discuss.

- Accented vs unaccented

- An accented NCT occurs in a strong metric position (“on the beat”).

- An unaccented NCT occurs in a weak metric position (“off the beat”).

- On-chord vs off-chord

- An on-chord NCT coincides with a change of harmony.

- An off-chord NCT does not coincide with a change of harmony.

- Chromatic vs diatonic

- Diatonic NCTs use only the notes present in the key-signature whereas chromatic NCTs have an accidental.

- As per usual, we will consider the leading tone in a minor key as diatonic.

- All types of NCTs can be either chromatic or diatonic, although some are extremely rare (such as a chromatic suspension).

- Diatonic NCTs use only the notes present in the key-signature whereas chromatic NCTs have an accidental.

- Ascending vs descending (passing tones only)

- This describes the direction created by the passing tone when combined with the chord tones on either side.

- Upper vs lower (neighbor tones only)

- Neighbor tones can be divided into two categories based on whether they are above or below the chord tone that they are embellishing.

One note on these labels: Because some methods for musical analysis only focus on music of certain periods (e.g. the Classical era), they may be overly specific in describing certain non-chord tones in a way that does not fully address the nature of the non-chord tone. For example, some texts say that suspensions must be accented, but because accented refers to a metric position (‘on’ or ‘off’ the beat) rather than a harmonic position, this is not always true in later styles. This is likely always true in the music of Mozart or even Beethoven, but it is not always true for the music of Gustav Mahler or John Lennon. It would be better to say that suspensions are always on-chord, because this allows for a suspension to happen in a weaker metric position. Harmony and rhythm exist independently, so we should use labels that help us understand all types of tonal music.

Passing tones, neighbor tones, and suspensions

Analyze the following chorale. We will use this as a framework to add a variety of NCTs.

The following exercise incorporates multiple examples of three types of NCT to create an (overly) embellished example. They are:

- passing tone

- neighbor tone

- suspension

Identify each of the non-chord tones in the following example by comparing it to the unembellished example above. You should be able to deduce to which classification each non-chord tone belongs by comparing the name (i.e. passing, neighbor, and suspension) to the motion around the non-chord tone. As you do so, create a definition of each type of non-chord tone using the terminology that we discussed above. (e.g. preparation, resolution, accented, etc.)

Conclusions

When we analyze non-chord tones, we label a single pitch that does not belong to the chord, however, we are actually classifying the motion between the non-chord tone and its surrounding pitches, and you can see this in these straightforward definitions:

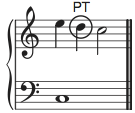

- A passing tone (PT) is a non-chord tone which is approached by step and left by step in the same direction.

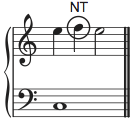

- A neighbor tone (NT) is a non-chord tone which is approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction.

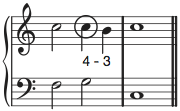

- A suspension (SUS) is a non-chord tone which is approached by static motion and resolves downward by step.

Let’s look at each of these in more detail. The following descriptions are lightly edited versions taken from Open Music Theory.

Passing tone (pt)

A passing tone is a melodic embellishment that occurs between two stable tones, creating stepwise motion. It is approached by stepwise motion and left by stepwise motion in the same direction. A passing tone can be either accented or unaccented as well as on-chord or off-chord.

The typical figure is chord tone – passing tone – chord tone, filling in a third (see example), but multiple adjacent passing tones can also be used to fill in the space between two chord tones, and these would be labeled by their number as appropriate–double passing tone (dpt), triple passing tone (tpt), or quadruple passing tone (qpt). The only time you can have a diatonic double passing tone is between the chordal fifth and root of a triad (e.g. sol-(la-ti)-do within a I chord). You can have a double passing tone to fill in a third if there are chromatic tones, and all triple and quadruple passing tones require chromatic pitches.

Neighbor tone (nt)

Like the passing tone, a neighbor tone is a melodic embellishment that occurs between two stable tones; however, a neighbor tone occurs between two instances of the same stable tone. It is approached by stepwise motion and left by stepwise motion in the opposite direction. Also like the passing tone, movement from the stable tone to the neighbor tone and back will always be by step. A neighbor tone can be either accented or unaccented, but unaccented is more common. It can also be either on-chord or off-chord.

Suspension (sus)

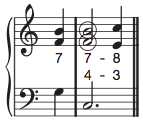

A suspension is formed of three critical parts: the preparation (accented or unaccented), the suspension itself (accented), and the resolution (unaccented). The preparation is a chord tone (consonance). The suspension is the same note as the preparation and will always be on-chord, which means that all suspensions require two chords, because the preparation will be on a different chord than the NCT itself. The suspension then resolves downward by step to the resolution, which occurs over the same harmony as the suspension.

Of note, it is a common misconception among students that a suspension is only present if you see a tied note. This is not true; the tone can be re-articulated. It only needs to follow the pattern of

- chord tone -> non-chord tone approached by static motion on a new chord -> resolution within the same chord

The suspension is in many respects the opposite of an anticipation (see the next topic, Unit 9b); if the anticipation is an early arrival of a tone belonging to the following chord, a suspension is a lingering of a chord tone belonging to the previous chord that forces the late arrival of the new chord’s chord tone. However, in composition and improvisation, the suspension must be treated with a great deal more care than an anticipation. The most common suspensions (and their resolutions) in upper voices form the following intervallic patterns against the bass: 9–8, 7–6, 4–3. (With the exception of 9–8, the pitch class of the resolution tone should never sound in another voice simultaneous with the suspended tone.)

Because suspensions can take many forms, we apply intervallic labels. When the suspension is in an upper voice, we always label the intervals of the suspension and its resolution against the bass meaning that the intervals will move from large to small (e.g. 4-3, 7-6, 9-8, etc.). When a suspended note is in the bass voice, however, we label the intervals against the most dissonant interval which means that the intervals will move from small to large (e.g. 2-3). When you measure a downward resolution in an upper voice against a lower voice, the intervals get smaller as the upper voice moves closer to the bass. When you measure a downward resolution against a higher voice, the intervals get larger as the bass moves away from the upper voice.

Of note, because we use the most dissonant voice to label suspensions in the bass, you will use the “2-3” label in the vast majority of this type of suspension. These intervals will be present for suspensions resolving to either the root or chordal third as long as the chord is complete. You are unlikely to encounter a suspension above a chordal fifth in the bass because of the usage rules of second inversion chords, and a suspension above the chordal seventh would just be the root of the chord–meaning that it is not a non-chord tone.

The most common suspensions are the 4-3, 7-6, 9-8 (2-1), and 2-3 suspensions, but others can and do occur regularly.

Retardations (RET)

The next example has taken the framework above and incorporated a new NCT: the retardation. How would you describe this? Which other NCT does a retardation resemble?

Conclusion (RET)

A retardation is essentially an upward-resolving suspension. It is almost always reserved for the final chord of a large formal division (or a movement), and it frequently appears simultaneously with a suspension (as seen in the picture above–the retardation is the upper-most voice). Like suspensions, retardations must be accented and on-chord, yet unlike suspensions, it is not necessary to label the intervals against the bass, although you may do so if you wish.

A few last notes

There are four other standard non-chord tones that we will discuss in the next topic, but we should clear up some common questions before moving on.

- First, some non-chord tones can occur within a single harmony or across two harmonies, meaning the preparation, NCT, and resolution are contained within one chord or spread across two. But other NCTs are restricted to one or the other. For example, a passing tone can be either within a single chord or spanning two chords, but suspensions and retardations can only happen across two chords; it is not possible to have suspension or retardation within a single chord. Any NCT with restrictions such as this will be noted in their descriptions, and it is imperative that you learn the context for each of the non-chord tones, so that you can quickly identify these issues.

- Once we have discussed all nine of the standard NCTs, you will be able to describe and analyze almost any combination of melodic intervals as they pertain to tonal harmony. Generally speaking, if you cannot come up with an analysis of a melody that accounts for each NCT into one of the nine categories, that means that you likely analyzed the harmonies incorrectly. As with even the most consistent of musical ideas, there will be occasional exceptions, but understanding your NCTs will be one of the easiest ways for you to make your analyses more effecient and effective.

- As we learn each of these non-chord tones, you will begin to notice these patterns in music, even when no NCT is present. If you would like to use a motion description for a chord tone, such as passing or neighbor, you can replace the word tone with the word figure. So a “passing figure” is a pitch that is approached by step and left by step in the same direction, but all three of the pitches that make up the preparation, passing tone, and resolution are chord tones.

- One of the most common questions about non-chord tones is whether a pitch should be written as a passing tone or a chordal seventh. For example, in the progression below, we have an imperfect authentic cadence, that starts as a simple triad, but then the alto voice moves to

fawhich could be analyzed as either a passing tone or a chordal seventh. So which would you choose? Is this a V chord with a passing tone or is this a V7 chord with no non-chord tones?- In this particular case, I would consider

faas part of the chord, because it is functioning as a chordal seventh. The chordal seventh is a tendency tone that typically resolves downward by step, and it is doing so here. If it resolved in another way (e.g. up by step), it might be a melodic passing tone and would therefore be not functional.

- In this particular case, I would consider

Regardless of whether you include the pitch as functional, the NCTs must always match the Roman numeral. In this scenario, if you choose to include the chordal seventh in your harmony, you only need to write the proper Roman numeral and inversion figure. If, however, you decide that the chordal seventh is just a passing tone, you must label it as a non-chord tone and write only V for the Roman numeral.

A final reminder!

As we first begin to study non-chord tones, the most important thing to remember is what the name “non-chord tone” emphasizes. NCTs must not belong to the chord. This is one of the most common mistakes for beginning analysts.