Integrated Music Theory 2021-22

Discussion 7b - Performing a Harmonic Analysis

Class Discussion

Process of harmonic analysis

- What you should try and do as early as possible is determine the harmonic rhythm, or how often the chord changes. This can happen every beat, every measure, or many other ways. The chorale we looked at in class is an example where the harmonic rhythm is every beat.

- Key: try not to rely as much on the key signature to figure out what key you’re in. Think of it as just one of many tools. There are other indicators of key–what chord does the section start on? What accidentals are repeatedly occurring in the section? Do these fit in with a major key or a minor one?

- Leadsheet: doing this first will save time in writing out your Roman numerals, especially if you are still unsure of what key you’re in.

- You do not need to repeat the Roman numerals for multiples of the same chord in a row.

Further Reading

The three common-practice harmonic functions

In common-practice music, harmonies tend to cluster around three high-level categories of harmonic function. These categories are traditionally called tonic (T), pre-dominant (P — sometimes referred to as subdominant, S), and dominant (D). Each of these functions has their own characteristic scale degrees, with their own characteristic tendencies. And each of these functions tend to participate in certain kinds of chord progressions more than others.

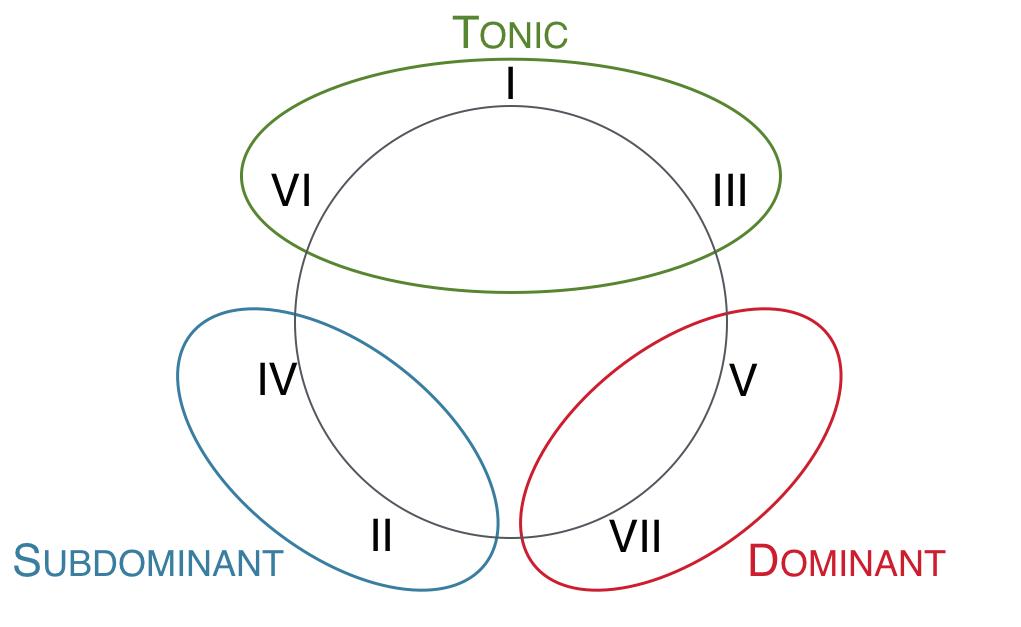

If you are already comfortable with Roman numerals, you can generally think of I, III, and VI as tonic, II and IV as pre-dominant, and V and VII as dominant. (Though, as you will see below, there is more to it than that.)

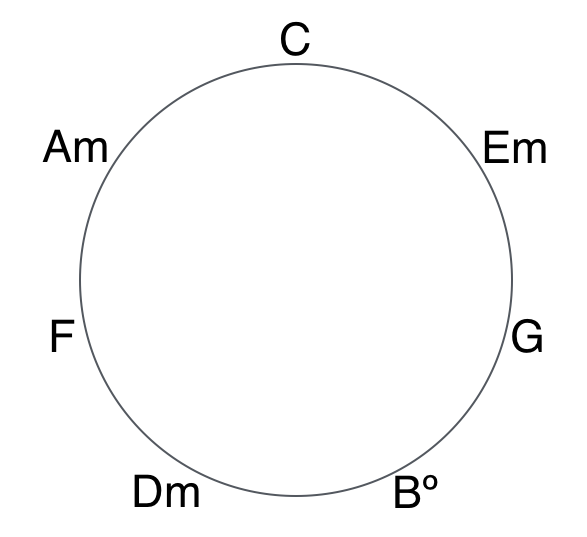

To visualize these functional categories, think of the usual triads in C major arranged on a circle of thirds. Note that each chord sits between the two triads that share the most tones in common — C major (C, E, G) sits between E minor (E, G, B) and A minor (A, C, E), both of which share two tones in common with C.

Convert these chords to Roman numerals (in C major), and we can see the functions. Since the function is determined by the tendencies of the tones that they share, and since on this graph chords are grouped together by notes they have in common, they are also grouped together by function.

Triads arranged on the circle of thirds, labeled by harmonic functions.

Interestingly, in common-practice music, a chord’s function can be determined solely by its internal characteristics (the notes that make up the chord). This is not true of all styles. For example, in pop/rock music a IV chord can exhibit very different functional tendencies depending on its context. But in classical music, simply knowing the notes in a chord is enough to determine its general harmonic function and the general tendencies of that chord and its individual notes.

The syntactic properties of these functions will be covered elsewhere. What follows simply explains how to determine the function of a chord in common-practice music with greater specificity.

Finding the function of a chord

Each of the three harmonic functions — tonic (T), pre-dominant (P), and dominant (D) — have characteristic scale degrees. Tonic’s characteristic scale degrees are 1, 3, 5, 6, and 7. Pre-dominant’s characteristic scale degrees are 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6. Dominant’s characteristic scale degrees are 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Ian Quinn (a music theorist at Yale University) further distinguishes these scale degrees, using the categories of functional triggers, functional associates, and functional dissonances. These categories help us understand the functional properties of chords whose scale degrees belong to more than one function, as well as how certain notes behave within a chord. They also help us understand which scale degrees are more or less characteristic of a function ― something that will help determine function when a complete chord is not present.

| function | triggers | associates | dissonances |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | 1 and 3 | 5 and 6 | 5 (if 6 is also present) and 7 |

| P | 4 and 6 | 1 and 2 | 1 (if 2 is also present) and 3 |

| D | 5 and 7 | 2 | 4 and 6 |

In terms of moveable-do solfège:

| function | triggers | associates | dissonances |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | do and mi/me | sol and la/le | sol (if la/le is also present) and ti/te |

| P | fa and la/le | do and re | do (if re is also present) and mi/me |

| D | sol and ti/te | re | fa and la/le |

To determine the function of a chord, find the function that includes all the scale degrees of a chord (regardless of chromatic alterations ― that is, treat ♯4 the same as regular scale-degree 4). If more than one function contains all the scale degrees, take the function with the most triggers in the chord.

There is one exception to this (for now): a chord with scale degrees 6, 1, and 3 is a special kind of tonic chord, called a destabilized tonic. Quinn uses the special functional label is Tx, rather than simply T, for this chord.

Also note that because the III7 chord’s scale-degrees do not wholly belong to any of the three functions, it can behave similar to T and D chords, depending on context. It is a rare chord in its diatonic form.

This handout will help you determine the function of a chord from the bass scale degree and/or the Roman numeral.