Integrated Music Theory 2019-20

Discussion 3a - Triads

Class Discussion

Using all the terminology we’ve learned so far, tell us how to…

ID Triads?

- M: M3 + m3 (P5 outside)

- m: m3 + M3 (P5 outside)

- d: m3 + m3 (d5 outside)

- A: M3 + M3 (A5 outside)

Note that all 3rds are either major or minor! Don’t even worry about diminished thirds.

Additional tips:

- Knowing your scales can help identify triads, especially in a key with lots of sharps or flats where many of the possible altered notes are double sharps or flats.

- Possible groupings for memorization

- M and A both “start” with a M3, m and d both start with a m3

- M and m are more familiar whereas A and d are newer and “weirder,” have altered 5ths

ID inversions?

- Root position = “a stack of thirds”

- Labeled using the intervals between the notes (not specific enough: what really matters?)

- Eliminating duplicates, extra octaves–what matters most is the bass/bottom note of the triad

ID closed vs open voicing?

- Closed voicing = closest notes can be notated together on a staff, open = spread out? (No: “spread out” is not specific enough)

- Closed voicing = voices within a 4th, open = voices larger apart than a 4th? (On the right track, but not quite!)

- Closed voicing = within an octave, open voicing = greater than an octave?

These are all good guesses, but closed voicing means stacking all chord members in ascending order without skipping over any of them. Open voicing is anything but that.

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

A chord is any combination of three or more pitch classes that sound simultaneously.

A three-note chord whose pitch classes can be arranged as thirds is called a triad.

To quickly determine whether a three-note chord is a triad, arrange the three notes on the “circle of thirds” below. The pitch classes of a triad will always sit next to each other.

Identifying and labeling triads

Triads are identified according to their root and quality.

Triad roots

To find a triad’s root, arrange the pitch classes on a circle of thirds (mentally or on paper). The root is the lowest in the three-pitch-class clump. Expressed another way, if the circle ascends by thirds as it moves clockwise, the root is the “earliest” note (thinking like a literal clock), and the other pitch classes come “later.”

Once you know the root, you can identify the remaining notes as the third of the chord (a third above the root) and the fifth of the chord (a fifth above the root).

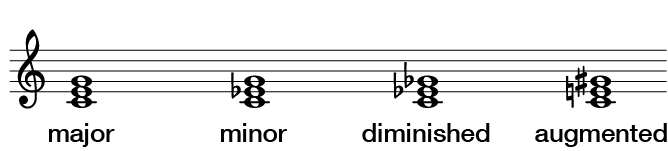

Triad qualities

To find a triad’s quality, identify the interval between the root and the other members of the chord. There are four qualities of triads that appear in major and minor scales, each with their own characteristic intervals.

- major triad: M3 and P5 above the root (as in do–mi–sol)

- minor triad: m3 and P5 above the root (as in do–me–sol or la–do–mi)

- diminished triad: m3 and d5 above the root (as in ti–re–fa)

- augmented triad: M3 and A5 above the root (as in me–sol–ti)

Building a triad

To build a triad on the staff, identify the root, quality, and bass note from the lead-sheet symbol. The root and quality will tell you what three pitch classes belong to the triad. For example, C+ tells you the root is C, and the quality is augmented. Since the quality is augmented, there is a major third above the root (E) and an augmented fifth above the root (G-sharp). Since there is no bass note appended to the lead-sheet symbol, the bass note is the same as the root: C. Write a C on the staff (in any comfortable register), then write the other chord tones (E and G-sharp) above the C (see the Caug triad in the above figure).

For Cm/E♭, the root is C, and the quality is minor. Since the quality is minor, there is a minor third above the root (E-flat) and a perfect fifth above the root (G). The slash identifies E-flat as the bass note. Write the E-flat on the staff. Then write a C and a G above it to complete the chord (again, see above).

When all the members of the triad are as close to the bass note as they can be, the chord is in what is called close position (C, Cm/E♭, and Cdim/G♭ above). When there are spaces between chord tones, the chord is in open position (Caug above). (In certain musical situations, only one of those positions will be useful or desirable.)

Listening to triads

Each triad quality has its own distinct sound, and to an extent that sound is preserved even when the chord is inverted (when the pitch classes are arranged so that a pitch class other than the root is in the lowest voice). As you practice identifying and writing triads, be sure to play the triads, both to check your analysis/writing and to develop the ability to identify chord qualities quickly by ear.

Inversions

Both bass lines and root progressions are important for the study and mastery of tonal harmony. Most of our work will focus on the bass lines, and what follows will help you analyze the root progressions present in any figured bass line. In other words, this will help you perform a Roman numeral analysis of a figured bass line.

Note that on the charts below, generic capital Roman numerals are provided.

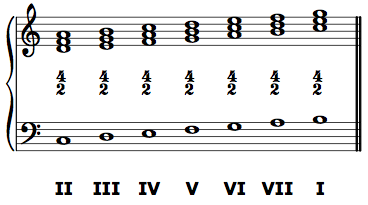

Chords of the fifth

In any chord of the fifth (“root position”: 5/3 or 7/5/3 chord), the bass note and the root of the chord are the same. The Roman numeral to be assigned to any chord of the fifth, then, is the scale degree of its bass note. If do is in the bass, the bass is scale-degree 1, and the Roman numeral is I. If re is in the bass, the Roman numeral is II. And so on.

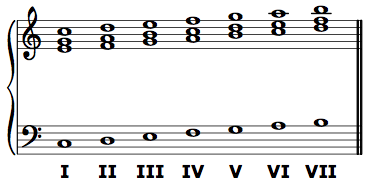

“First-inversion” chords of the sixth

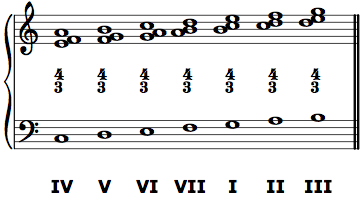

Chords of the sixth that take the figures 6/3 or 6/5/3 are first-inversion chords. They are so named because the third of the chord (the next chord member above the root) is in the lowest voice. However, thinking about inversions while performing an analysis can be cumbersome. It is often simpler to remember that if the figure is 6/3 or 6/5/3 (or an abbreviation such as 6 or 6/5), the root of the chord is the sixth above the bass. If mi is in the bass, and the figure is “6”, the root is do, and the Roman numeral is I. If fa is in the bass and the figure is “6/5”, the root is re, and the Roman numeral is II. And so on.

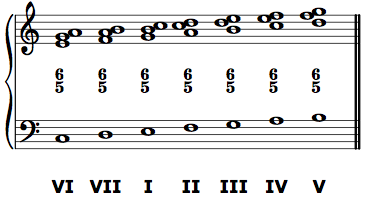

“Second-inversion” chords of the sixth

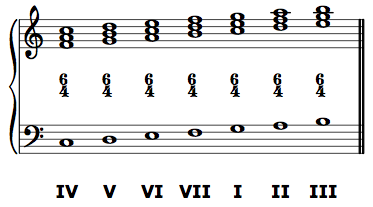

Chords of the sixth that take the figures 6/4 or 6/4/3 (or an abbreviation such as 4/3) are second-inversion chords. They are so named because the fifth of the chord (the second member of the chord above the root) is in the lowest voice. Again, it is often simpler to remember that for 6/4, 6/4/3, and 4/3 chords, the root is the fourth above the bass. If re is in the bass, and the figure is 4/3, the root is sol, and the Roman numeral is V.

“Third-inversion” chords of the sixth

Chords of the sixth that take the figure 6/4/2 (or its abbreviation 4/2 or simply 2) are third-inversion chords. Their root is a second, or a step, above the bass. The most common 4/2 chord has fa in the bass, and sol is its root, making its Roman numeral V.