Integrated Music Theory 2022-23

9b Lesson - Non-chord Tones, Part 2

NOTE: The full descriptions below of each type of non-chord tone are from the online textbook, Open Music Theory, although each has been edited to suit this textbook’s terminology and purpose. If you have not had a chance to check out Open Music Theory in the Further Reading sections from the previous units, please take the time to do so. It is an excellent resource!

Non-chord tone recap

Understanding non-chord tones is critical for increasing the accuracy and speed of your tonal analysis. When looking at pieces of music, specifically those that have complicated textures, you will often face difficult decisions about which tones are functional to the harmonic progression and which tones are embellishing those functional tones. If you know the shapes that chord tones and their embellishments form, you can separate chord tones from embellishments by simply looking for common patterns.

We will use the same simple progression that we used in the previous topic as a template for demonstrating non-chord tones. You can review the analysis here.

Non-chord tones, part 2

Compare the examples below to the original progression to determine what has changed. As you do this, use the the three characteristics discussed in the previous topic–preparation, NCT, and resolution–to create a definition for each NCT. Once you have a working definition, see if the other other descriptors (e.g. upper/lower, ascending/descending, chromatic/diatonic, on-chord/off-chord, or accented/non-accented) can be applied to each NCT.

Neighbor Groups (NG) - also referred to as Double Neighbor Tones (DN)

The following example contains multiple neighbor groups.

- How would you define a neighbor group?

- How does the neighbor group relate to a neighbor tone?

- What restrictions, if any, could you imagine placing on a neighbor group?

Conclusions

Like neighbor tones, a neighbor group, also known as a double neighbor tone, begins and ends on the same chord tone. Between those two instances of the chord tone are two embellishing tones–one a step above and the other a step below the stable tone being embellished. Though individually we may consider each of the two embellishing tones to be incomplete neighbor tones, the two tones of the neighbor group balance each other and create a contiguous whole, with the overall stability of a complete neighbor. A neighbor group is typically unaccented and off-chord, although it could be both accented and on-chord. It may occur within a single chord or across two chords, and either the upper or lower neighbor can be chromatically altered to strengthen the resolution.

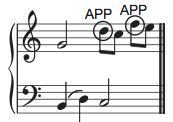

Appoggiaturas (APP)

In the same way that suspensions and retardations are often grouped together, appoggiaturas and escape tones are as well. The following two examples include NCT appoggiaturas and escape tones as well as appoggiaturas figures and escape tone figures. Use the example below to answer the following:

- What is the definition for both of these non-chord tones?

- What do they have in common and why are they grouped together?

- What major difference does the term “figure” imply when used in referencing non-chord tones? Do you think that “figure” could be applied to any of the previous NCTs that we have studied?

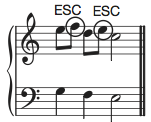

Escape tones (ET)

Conclusions

An appoggiatura is a non-chord tone that is approached by leap, and followed by step in the opposite direction.

An escape tone, or echappée, is a non-chord tone that is approached by stepwise motion and left by leap in the opposite direction.

In the examples above, I have labeled some of the NCTs as “figures”. The term “figure” can be used to describe a melodic pattern that follows the shape of a classification of non-chord tone–such as a passing tone or an appoggiatura–but all pitches are actually chord tones. This is useful when trying to describe melodies in an objective manner. For example, a melody could be described as having a passing figure if the melody has a stepwise movement continuously in one direction, even if every note belongs to a chord.

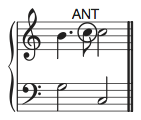

Anticipations (ANT)

Conclusions

An anticipation is a non-chord tone that occurs immediately before a change of harmony and is left by static motion. Or more simply stated, an anticipation is a chord tone that arrives a bit too early. It is most often approached by stepwise motion, but you will occasionally find examples that leap to the anticipation.

This NCT must be a chord tone taken from the chord to which it resolves, meaning that it must be a chord tone from the new harmony. The static motion between the NCT and its resolution means that you may consider this related to both suspensions and retardations, although unlike suspensions and retardations, this is always an unaccented, off-chord NCT with static motion occurring after the NCT rather than before. It is typically found at the ends of phrases and larger formal units.

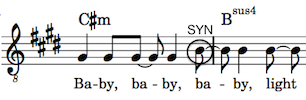

Syncopation versus anticipations

Some theorists classify syncopated rhythmic figures as separate from anticipations, but this is more a discussion of re-articulation. For those that classify these differently, syncopation occurs when a rhythmic pattern that typically occurs on strong beats or strong parts of the beat occurs instead on weak beats or weak parts of the beat. Like the anticipation, the syncopated note is an early arrival–it tends to belong to the chord on the following beat. Unlike the anticipation, the syncopation is tied into a note in that chord and is not rearticulated. Rather than anticipating a note in the chord that follows, a syncopation is simply a disjointed and repeated arrival of the chord itself. Of course, you should consider context when making this decision as this difference is subtle, but if there is a pattern of syncopated rhythms in a passage, you could be more likely to label syncopation for the passage as a whole, rather than many anticipations.

Pedals (PED)

Pedals, often referred to as pedal tones or pedal points, most often occur in the bass voice but can occur in any voice. They can be difficult to spot if the texture is broken into arpeggiated chords, so it may be necessary to reduce a complicated texture down to block chords to more easily find the pedals.

Conclusions

Pedals are approached by static motion and left by static motion; essentially, this is a note that refuses to leave regardless of whether it belongs to the chord. Pedals are one of the most interesting non-chord tones because they have a dual nature–they create some of the strongest dissonances in tonal harmony, but their repetitive nature provides an unusual stability. As a pedal continues, it will often alternate between acting as a chord tone and non-chord tone, so it can be helpful to label the chord tones as “pedal figures” to show the continuation of the pedal as demonstrated in the first measure above.

Incomplete Neighbor Tone (INT) and Incomplete Neighbor Group (ING)

While less common than those above, you will occasionally encounter non-chord tones that are approached by leap and left by step in the same direction; resembling an appoggiatura but not resolving in the opposite direction. For our analyses, we will label these as incomplete neighbor tones, although some theorists use this term to refer to appoggiaturas and escape tones as well. Broadly speaking, you should not resort to an incomplete neighbor tone NCT unless you have exhausted all other options, because it is far more likely that this melodic shape is part of a chordal skip rather than an actual NCT. You should always check for other harmonic possibilities before committing to an INT.

There is also an additional variation of incomplete neighbor tones called incomplete neighbor groups (ING). An incomplete neighbor group occurs when a chord tone is approached by two pitches as if they were a part of a neighbor group–meaning one NCT a step above and one NCT a step below–but unlike a neighbor group, the first instance of the chord tone is not present. Like incomplete neighbor tones, these should be a last resort in your analyses, but they occur often enough that we need this label.